Arthur Patterson on Crypto, Cogs, and the Search for Meaning

Accel’s co-founder reflects on the venture game and the power of curiosity

This week, we’re talking:

Why curiosity, tenacity, and reinvention matter more than pedigree — and sometimes, the messiest energy is the most transformative 🤔🏋🏾♀️🐛

The through line in every hype cycle? People want to believe. Ideology fills a void that used to belong to religion — and venture sometimes fuels the fantasy. 🔮 🙏🏻

When boredom replaces pain as the dominant affliction of modern life, do we get peace or do we get people desperately seeking meaning in all the wrong places? 🍰📱💤

Financial anxiety, class blindness, and the comfort class designing policy for a reality they’ve never lived. 🏦📉🧘♂️

Is open-mindedness a virtue or a neurobiological privilege? New research suggests ideological rigidity isn’t just stubbornness — it’s hardwired. 🧠⚖️🔐

After turning down a $23B offer last year to chase an IPO, Wiz just signed the dotted line for $32B in Google’s biggest acquisition ever 🚀📉🧩

My Take:

Though this conversation happened in 2022, it keeps resurfacing in my mind. Some of the examples aren’t as timely as they were then but I think Arthur’s major points hold. Curious if you agree.

Arthur’s Take:

Tom Chavez: You co-founded Accel with Jim Swartz in 1983—when venture capital was just barely a state of mind. I’m curious if you could talk a little bit about the factors you think led to Accel’s success.

Arthur Patterson: Well, we had the good fortune of starting a new fund at a time when the market was big enough, but we were small and nimble enough to go our own way. And the way we went was specialization. The existing firms had taken a broad approach to venture, and by the time we got into the game, most firms’ investments were spread across industries. I had done a handful of software deals and had a gut sense that that was where I wanted to be.

Tom Chavez: So you took advantage of being new to the market.

Arthur Patterson: Exactly. We were a startup—we had a clean start. And as we see every day, there’s nothing quite like a clean start.

Tom Chavez: Why do you think specialization was such a successful route for you to go?

Arthur Patterson: By focusing only on deals in one space, we could really understand and assess what the best opportunities were. It let us take a much more systematic approach to investing—something the bigger firms, with their portfolios bogged down across multiple sectors, just weren’t in a position to do.

Tom Chavez: And that focus on specialization became the start of Accel’s thesis-based approach?

Arthur Patterson: That was the beginning of what we later called the “Prepared Mind”—the idea that when an entrepreneur walks through the door, you should already understand 90% of the business. The entrepreneur brings the critical 10%, but if you don’t know the other 90%, you won’t recognize the opportunity when it’s right in front of you.

“Being an early-stage entrepreneur is a long and lonely process. It might go on for five years or more. You have to be genuinely curious about the problem you’re solving to stick with it through all the highs and lows. You don’t need to be a genius, but you do need to be curious.” -Arthur Patterson

Tom Chavez: And you started seeing that play out.

Arthur Patterson: My best deal was a perfect example. I’d been investing in the internet service industry and understood what a pain point billing was at the time. The CEO of this company had been turned down by all the major firms—they got caught up in the surface details and missed the significance of the opportunity. They thought the CEO didn’t have the right background.

Tom Chavez: And that was Portal?

Arthur Patterson: Correct.

Tom Chavez: You’re saying others got hung up on the CEO. What do you look for in a CEO?

Arthur Patterson: I look for people who are sufficiently curious.

Tom Chavez: Say more.

Arthur Patterson: Being an early-stage entrepreneur is a long and lonely process. It might go on for five years or more. You have to be genuinely curious about the problem you’re solving to stick with it through all the highs and lows. You don’t need to be a genius, but you do need to be curious.

Tom Chavez: You started Accel in 1983. I’d love to talk about company building today compared to back then.

Arthur Patterson: The fundamentals haven’t changed.

Tom Chavez: But the amount of capital has. The velocity and volume of companies. The things that used to take nine months now seem to take nine days. Everything moves so quickly—competitors included.

Arthur Patterson: The clock speed has picked up in a very liquid market—that’s true. But the fundamentals of company-building haven’t picked up in the same way. What people generally miss is that this is all a supply problem. Venture capitalists like me think we’re important. Entrepreneurs like you think you’re important. But we’re all just cogs in a wheel. Some more talented than others, sure—but cogs nonetheless.

New technologies and shifting social norms create X number of real opportunities. That number doesn’t change. The iPhone would’ve been invented in the Soviet Union—it just would’ve taken another 50 years. What entrepreneurism in the U.S. does is accelerate the realization of those opportunities. And that’s powerful.

Tom Chavez: Cogs or no, there’s still a human dimension to all this.

Arthur Patterson: Of course.

Tom Chavez: So let’s talk about the human side, in the context of something like crypto. Hindsight’s 20/20, but I do like to point out that I never bought a single Bitcoin. Maybe I’m a Luddite, but crypto always seemed like breathless mumbo-jumbo to me. And yet so many people got swept up in an idea that didn’t really hold up to scrutiny.

Arthur Patterson: Human beings are very susceptible. They want to believe.

Tom Chavez: Even venture capitalists?

Arthur Patterson: We’re all human. It can be hard to keep your head. I remember in 1997, people looked at Yahoo! and said, “Really? A search engine?” Then it went to $10 billion. And the reaction was, “Okay, maybe we shouldn’t be so skeptical.” So people opened their wallets. That’s how it happens. And especially now—people want to believe. They want to belong. Crypto. Wokeism. Nationalism. They’ve all become belief systems. That need to belong becomes a kind of hunger. You see it across the board—people looking for something to believe in. Wokeism, nationalism, crypto—these are belief systems that fill a void. Religion is too slow. Nationalism feels tired. Crypto promised meaning, rebellion, transformation—and easy money.

Tom Chavez: And you didn’t need to build anything.

Arthur Patterson: Exactly. It was the perfect speculative vehicle. No customers to disappoint. No hardware to ship. No management headaches. Just tokens and marketing. And it all got turbocharged when the Treasury decided crypto was an asset, not a currency. That effectively legalized counterfeiting. Suddenly there were 14,000 people printing money.

Tom Chavez: If only we’d started our own coin.

Arthur Patterson: We’d be on a yacht somewhere.

Tom Chavez: All of this feels like a good moment to ask you something I’ve waited 25 years to ask. Back at Rapt, early days, you used to tease me in board meetings—“What’s the business plan this time?” I was a puppy, still figuring it out. Why didn’t you fire me?

Arthur Patterson: Because you were the company. There wasn’t enough business there to attract someone else. But more importantly, you kept moving. You kept trying, repositioning, learning. You didn’t quit.

Tom Chavez: You once called it “demonic energy.”

Arthur Patterson: I meant it in a good way. You had this intensity, this force of will. You were possessed—in the best sense. You took responsibility. You reinvented the company over and over. That’s what it takes. It’s not the venture guy who wills the company into existence—it’s the founder.

Tom Chavez: We use that phrase all the time now. “Bring the demonic energy.”

Arthur Patterson: You earned it.

Tom Chavez: When you zoom out—across your career—what are you most proud of?

Arthur Patterson: The profession. We do well by doing good. We help entrepreneurs. We create jobs. We push the economy forward. I honestly believe that without entrepreneurs, without startups, we’d be stuck with giant, sluggish institutions. We’d be living in something that looked a lot more like Russia. Silicon Valley—entrepreneurism—has changed the world.

Tom Chavez: Last question. When you think about your biggest hits—and your biggest misses—is there a common thread?

Arthur Patterson: The good ones always start with a good idea. It doesn’t have to be a perfect team. But great ideas attract great people. Weak ideas drive them away. Sometimes the timing’s just off. I’ve had ideas that were solid—but ten years too early. The market wasn’t ready. And that’s one of the hardest things to judge.

Tom Chavez: And yet you’ve stayed in it. Decade after decade.

Arthur Patterson: You stay curious. You try to see clearly. And when that demonic energy walks through your door—you recognize it.

My Media Diet:

What the Comfort Class Doesn’t Get By Xochitl Gonzalez via The Atlantic 🏦📉🧘♂️

What we have is a compounded problem, in which people with generational wealth pull the levers on a society that they don’t understand. Whether corporate policies or social welfare or college financial aid, nearly every aspect of society has been designed by people unfamiliar with not only the experience of living in poverty but the experience of living paycheck to paycheck—a circumstance that, Bank of America data shows, a quarter of Americans know well… Exacerbating this problem is widespread class dysmorphia. One reason so many well-off Americans feel capable of opining about less well-off Americans is because they don’t realize that they are, in fact, well-off in the first place. The explosion of the American billionaire class—from 272 individuals in 2001 to 813 in 2024, according to Forbes—has made millionaires feel relatively poor. There are more of them too. The number of Americans worth $30 million or more grew by 7.5 percent in 2023 alone. And still, according to a survey of millionaires done that year, two-thirds of them did not consider themselves wealthy.

Ideology May Not Be What You Think but How You’re Wired by Matt Richtel via NYTimes 🧠⚖️🔐

Rigid thinkers tend to have lower levels of dopamine in their prefrontal cortex and higher levels of dopamine in their striatum, a key midbrain structure in our reward system that controls our rapid instincts. So our psychological vulnerabilities to rigid ideologies may be grounded in biological differences. In fact, we find that people with different ideologies have differences in the physical structure and function of their brains. This is especially pronounced in brain networks responsible for reward, emotion processing, and monitoring when we make errors. For instance, the size of our amygdala — the almond-shaped structure that governs the processing of emotions, especially negatively tinged emotions such as fear, anger, disgust, danger and threat — is linked to whether we hold more conservative ideologies that justify traditions and the status quo.

The West is Bored to Death by Stuart Whatley via New Statesmen 🍰📱💤

American greatness has produced a society whose members know not what to do with the freedom and abundance that earlier generations secured. We are now witnessing the squandering of this inheritance, and it is even more idiotic and vulgar a spectacle than anyone would expect.

Google to acquire cloud security startup Wiz for $32 billion after deal fell apart last year by Samantha Subin via CNBC 🚀📉🧩

Last year, Wiz walked away from a potential $23 billion acquisition by Google and told employees that it would pursue an IPO instead. However, the IPO market has yet to open in a significant way since deals slowed to a trickle starting in 2022, and tech companies have expressed optimism that the Trump administration will open the door to large acquisitions after a difficult four years under President Joe Biden.

News from the Hive:

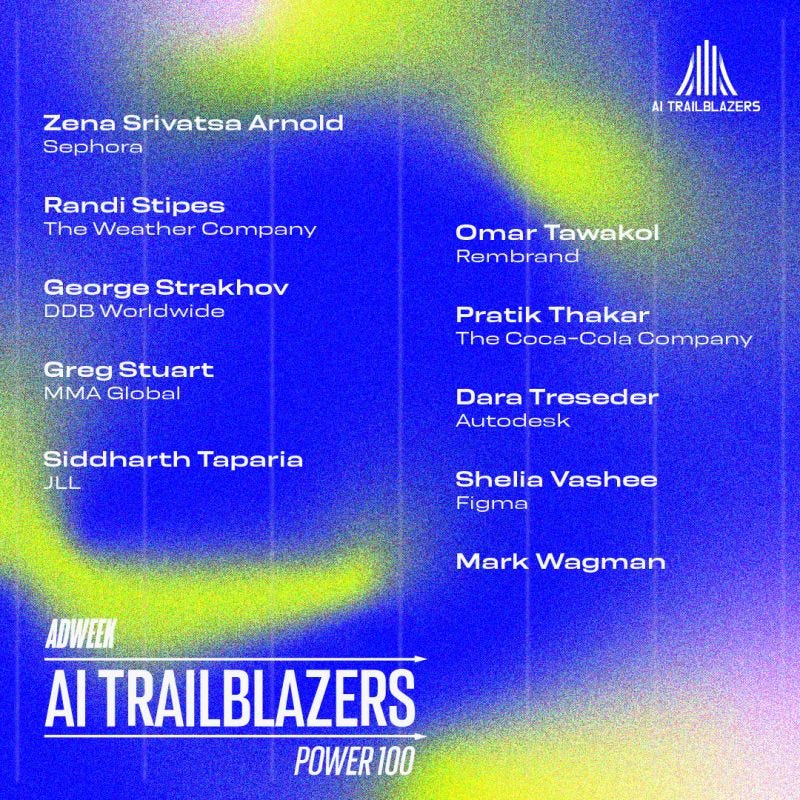

My partner Omar Tawakol being an AI trailblazer? Old news to me. But hey, stoked the rest of the world is catching up. AdWeek’s AI Trailblazers Power 100? We’ll take it.