Dead Metaphors Cost Billions

Capital doesn’t chase reality. It chases stories. The winners know when it’s time to tell a new one.

This Week, We’re Talking:

How metaphors create investment blind spots because capital flows toward familiar patterns and well-understood concepts, not alien possibilities.

Capital doesn’t chase reality, it chases stories. You can use that to your advantage.

A picture so mind-bogglingly wild that I thought it was an illustration ripped from The Onion. (it wasn’t.)

My Take:

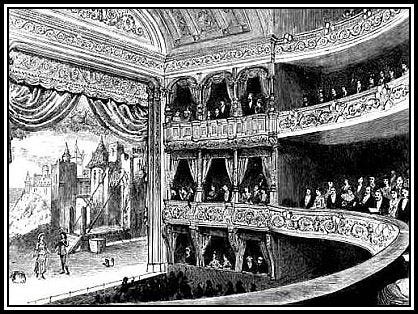

Imagine London, December 1881. The Savoy Theatre has just been rebuilt, and impresario Richard D’Oyly Carte is about to open his latest Gilbert & Sullivan opera. But while the cast lingers off-stage, the real stars hang above it: hundreds of incandescent bulbs. Tonight, the Savoy will become the first public building in the world lit entirely by electricity. The packed house murmurs. Gaslight they know. Just flame in a globe. Electricity feels like bottled lightning. To calm the fear, D’Oyly Carte, ever the showman, steps forward and smashes one of the glowing bulbs. No explosion. No flame. Just glass at his feet. He assures his audience that the lamps “consume no oxygen, and cause no perceptible heat.” The crowd exhales. It is not sorcery or danger. It is simply… light.

That was the metaphor that stuck: electricity as better lighting. It helped calm fear and spur adoption, but it also obscured the far greater revolution electricity was about to unleash.

This is the paradox of metaphors. They are essential at first: they make the strange legible and the scary familiar. But once they ossify into dogma, we fail to recognize them as metaphors at all. And when that happens, capital gets trapped by yesterday’s story.

And here’s the dangerous twist: the metaphor works both ways. We don’t just describe minds as computers. We then expect computers to have minds.

Cognitive metaphors create investment blind spots because capital flows toward familiar patterns and well-understood concepts, not alien possibilities.

In God, Human, Animal, Machine, Meghan O’Gieblyn reveals how completely metaphors capture our thinking. The brain-as-computer metaphor became so pervasive that neuroscientists literally cannot describe human behavior without it. We “process” ideas, “store” memories, “retrieve” information, forgetting these are metaphors, not biological realities. When psychologist Robert Epstein challenged researchers at a top institute to account for human behavior without computational language, they couldn’t do it.

And here’s the dangerous twist: the metaphor works both ways. We don’t just describe minds as computers. We then expect computers to have minds. We say that AI “understands,” “reasons,” and “learns” when these systems are actually doing something entirely different. The framework colonizes both directions, creating a feedback loop that blinds us to what’s actually going on.

This same cognitive trap shapes what entrepreneurs imagine and how investors allocate capital. Founders dream up what fits the frameworks, nomenclature, and terms already familiar to investors. “Uber for X” became a Silicon Valley cliché because it was a shorthand that snapped to VCs’ mental models. The internet as “stores” felt natural because everyone understood retail. Platforms, network effects, and data moats, meanwhile, were initially alien concepts that didn’t map to existing categories.

Metaphors are useful because they inspire and evoke the things we seek, the problems we care about. They grease the skids of a productive conversation when you’re not quite sure what you mean. But if we’re overtaken by them, they constrain thinking and impose boundaries around what’s possible.

Consider the evidence:

The internet as “stores.” Investors poured billions into e-commerce fronts like Pets.com, missing the platform play entirely. Amazon wasn’t just a better bookstore, it became a marketplace, logistics machine, and cloud infrastructure pioneer. The “store” metaphor blinded VCs to everything that didn’t look like retail – or the internet version of it, e-retail. Big ups to Bezos for throwing out the preexisting framework and inventing his own.

Cloud as “storage.” For years, the cloud was pitched as a cheaper hard drive in the sky. That metaphor guided capital toward simple file-sharing services while the real prize lay in elastic compute and infrastructure. AWS, Azure, and GCP — now worth hundreds of billions — barely resembled “storage” at all. Snowflake gives it away for free as a set up for the main attraction – compute.

CRM as “horizontal tools.” The early frame for customer relationship management was generic software that could serve everyone. But the real breakout came from vertical specialization. Veeva built CRM tailored to pharma, with regulatory workflows and compliance baked in — and today commands a multi-billion dollar valuation. The horizontal “CRM” metaphor hid the opportunity for vertical reinvention.

Mobile as “smaller computers.” The PC metaphor led investors to fund mobile versions of desktop software. Meanwhile, Apple built something unprecedented: the App Store economy, location-aware services, and always-connected computing that had no desktop equivalent.

Streaming as “internet TV.” Traditional media companies saw Netflix as just another cable channel. They missed that streaming was actually a global direct-to-consumer distribution platform that collapsed geographic licensing and reshaped entertainment economics entirely.

Capital doesn’t chase reality. It chases stories. The biggest arbitrage belongs to those who know when it’s time to bury a dead metaphor and create the next one.

Of course, some metaphors guide capital efficiently. Marc Andreessen’s “software eating the world” proved prescient. The “platform” metaphor, once we knew what it actually meant, helped investors spot network effects across industries. Reid Hoffman’s metaphor of startups as “jumping off a cliff and assembling a plane on the way down” captures the entrepreneurial reality better than business school frameworks ever could.

But these are living metaphors that evolve with new information. Dead metaphors calcify into doctrine.

The current risk is AI as “robot butler.” We picture Alexa taking notes, ChatGPT drafting emails, copilots coding at our side. Helpful assistants. This channels investment toward chatbots and personal productivity tools. But the biggest returns will flow to orchestration layers, inference infrastructure, and decision systems that don’t resemble “butlers” at all. Companies building AI that doesn’t pretend to think like humans, but instead accomplishes things that humans alone never could.

Every calcified story becomes a broken compass.

Nearly 150 years ago, D’Oyly Carte understood the moment and his role in it. In 1881, people needed reassurance that electricity was safe illumination, not dangerous sorcery. The metaphor served its purpose: it calmed fear and enabled adoption.

But the entrepreneurs who saw past “better lighting” built the electrical grid, urban transit, mass communication, and industrial automation.

Capital doesn’t chase reality. It chases stories. The biggest arbitrage belongs to those who know when it’s time to bury a dead metaphor and create the next one.

Every great technology begins with a story. The generational companies are built by the entrepreneurs who recognize it as a story, and decide to tell a different one.

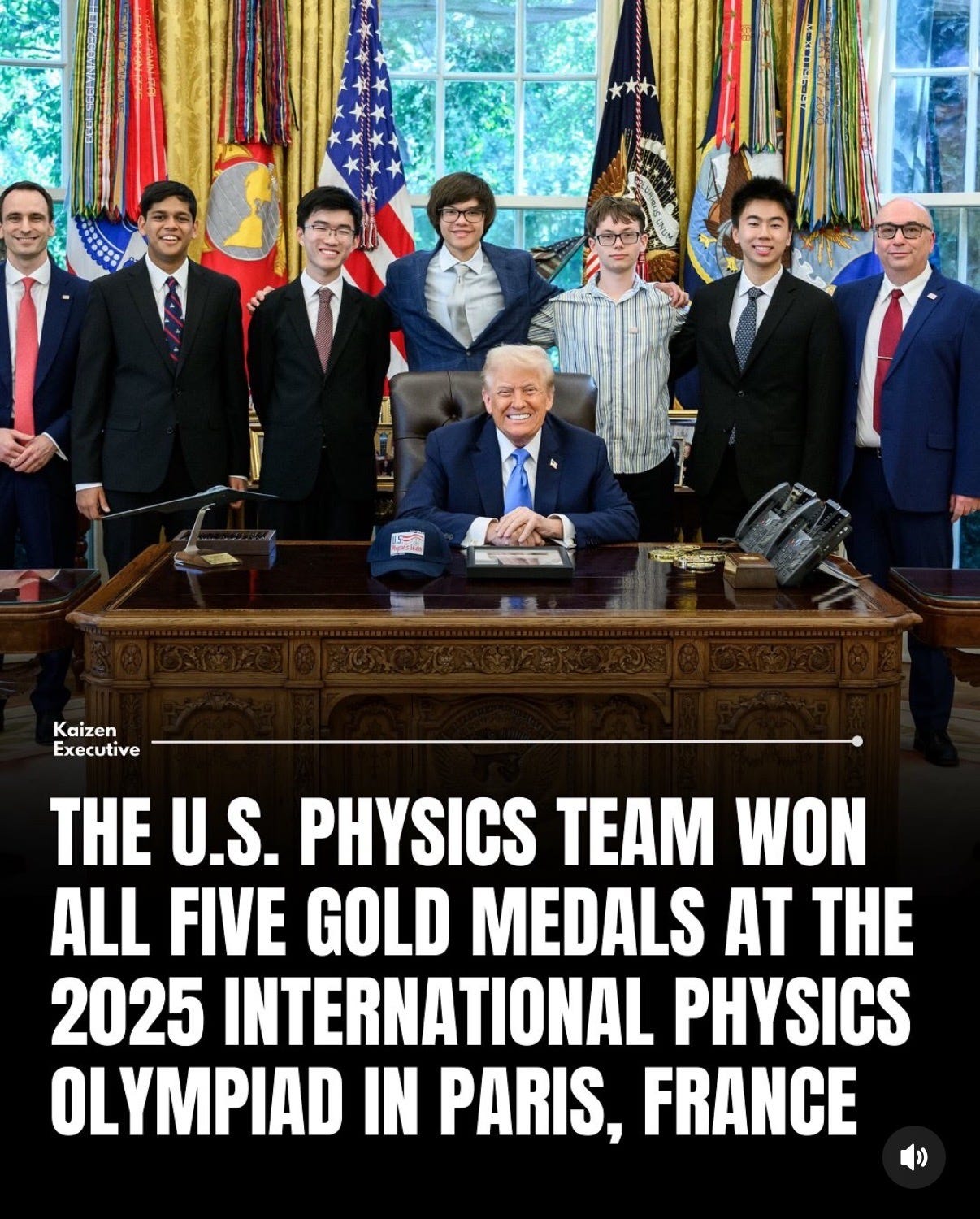

Picture of the Week:

The U.S. Physics Team just swept the International Physics Olympiad. They won every single gold medal.

And how did America celebrate? By cutting science funding, banning books, telling immigrant families like the ones raising our champions to get the hell out, and giving them a commemorative photo op with a guy who thinks “windmills cause cancer.”

Reporters pointed out the obvious: these kids are of Chinese, Indian, and Russian descent. In other words, this photo is Stephen Miller’s idea of a night terror — brown and immigrant kids getting an invite to the White House with gold medals around their necks instead of a one-way ticket to Rwanda with shackles around their wrists.

Ya gotta admit, the photo is hilarious, or just absurd.

I’ve said before that we’re eating the seed corn. That has never been truer. But eating the seed corn never looks catastrophic at first. The harvest looks fine. The medals shine. You can point and say, “see? we’re winning!”

But you’re NOT. You’re burning through what earlier generations invested in: immigrant families who believed in opportunity, schools that still funded science, a culture that once valued intellectual achievement.

By the time the pipeline dries up and talent goes elsewhere, it will be too late to fix.

So yeah, enjoy the photo op. It’s a commemorative shot of the last good harvest before the fields turn to dust.